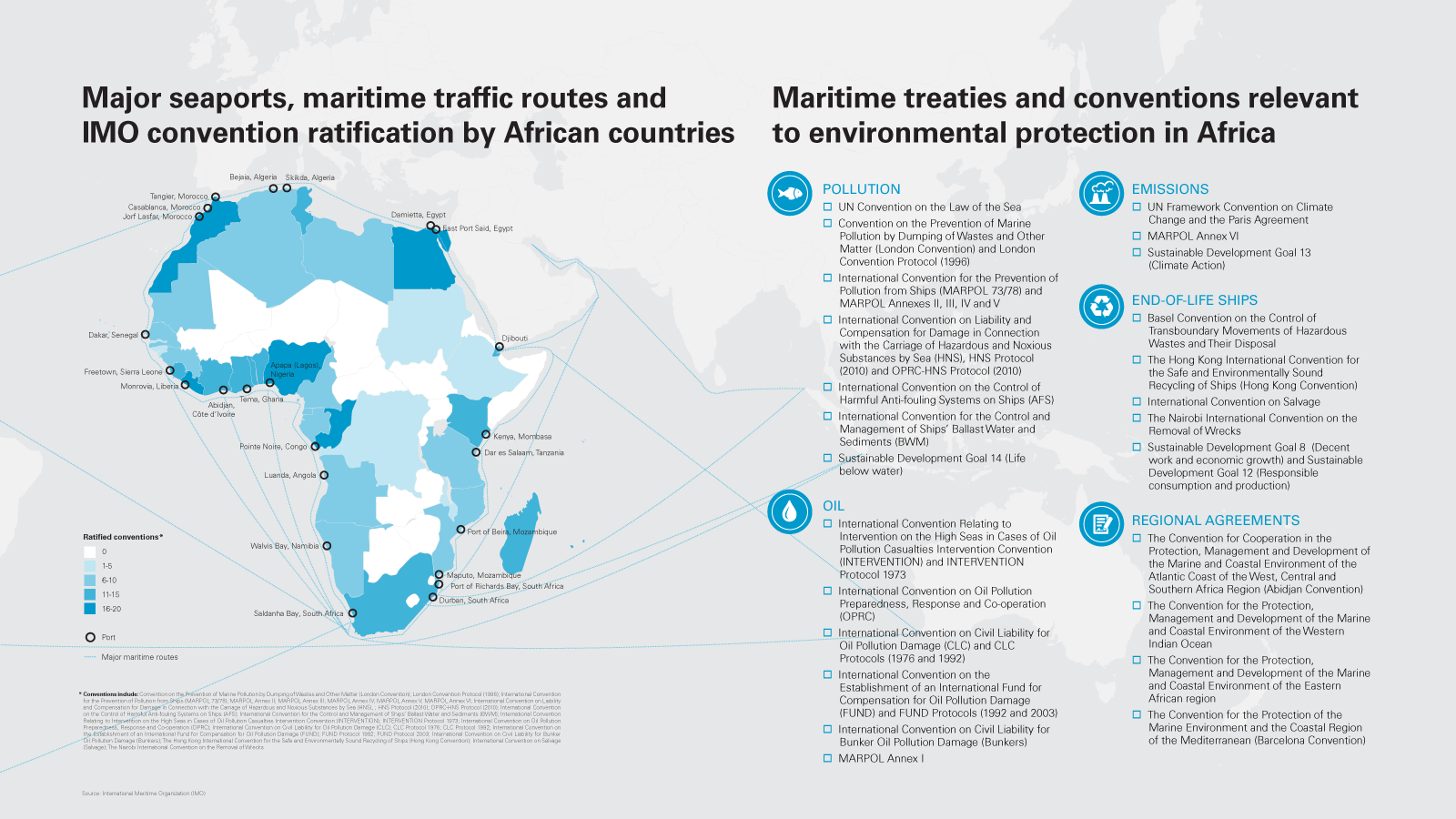

Some of the most important global sea lanes pass the continent of Africa. Major routes navigate the Cape of Good Hope between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, through the Red Sea and east-west through the Mediterranean Sea. Although Africa's own maritime transport sector remains relatively undeveloped, more than 90 percent of all imports and exports in Africa are facilitated by sea through ports along the coast.1 Africa is also home to one of the world's largest shipping registries. The Liberian Registry covers 11 percent of the world's oceangoing fleet.2

Issues concerning marine management in Africa are being tackled head-on by a range of international agreements. There are already four regional agreements across Africa that collectively seek to protect, manage and develop the marine and coastal environments of Africa and the Western Indian Ocean. These agreements have been widely endorsed. Almost all African costal states have signed at least one regional agreement, and only three have not signed any regional agreements. Institutions such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) are also actively creating new international agreements and protocols to address environmental issues such as marine pollution, oil spills and emissions from the shipping industry. IMO agreements and protocols are regularly updated in order to keep up to speed with new environmental challenges and the latest available scientific evidence. In so doing, the IMO has opened up pathways for African coastal states, shipping registries and ports to innovate and meet the challenges of sustainable development.

Ships that comply with green standards are more likely to be exempt from environmental taxes and fines, which could represent considerable savings over the operational life of a ship.

Africa's growth in the maritime industry highlights the potential for positive impacts on its socioeconomic development, especially of coastal states, but it also poses challenges. As Africa's maritime sector grows, with increasing marine traffic and cargo volumes through its ports, so does the potential for heavier environmental and social impacts. In this context, nascent businesses have an opportunity to ensure that, by complying with international standards from the outset, their operations will help to develop a maritime industry that conforms to environmental and social sustainability practices that will benefit current and future generations of Africans.

GREEN SHIPPING

Green shipping is indicative of the strides made in the industry to address its various impacts on human health and the environment. It addresses the preservation and protection of the global environment from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other pollutants generated by the industry and contributes to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In practice, the "green" standard entails compliance with the major IMO pollution-related conventions and their protocols that many coastal African countries have ratified.

The IMO commitment to sustainable development is designed to encourage innovation and technology transfer. The uptake of eco-friendly ship design by forward-thinking companies has increased over the past few years, with more companies producing and using eco-friendly ships as part of their operations. As marine pollution becomes more heavily regulated, investment in new ships that are compliant with current (and anticipated future) IMO regulations is becoming a competitive advantage. Ships that comply with green standards are considered more likely to be exempt from environmental taxes and fines, which could represent considerable savings over the operational life of a ship. In effect, the higher the green standard of the ship at the beginning of its life, the longer its operational life may be without the need for potentially expensive retrofitting. In addition, compliant ships are considered inherently more fuel-efficient, which also contributes to substantial operational cost savings.

MARINE POLLUTION

20%

of the sources of plastic pollution are marine-based, through both legal and illegal dumpingGreyer, R. (2017) "Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made,"Science Advances

With more than 75 percent of the planet covered by water, marine pollution is one of the most intractable global environmental challenges, and one the world will face for many generations to come. Shipping now accounts for the majority of the world's trade transportation, and the sheer volume of freight being transported means that a certain level of marine pollution is inevitable.

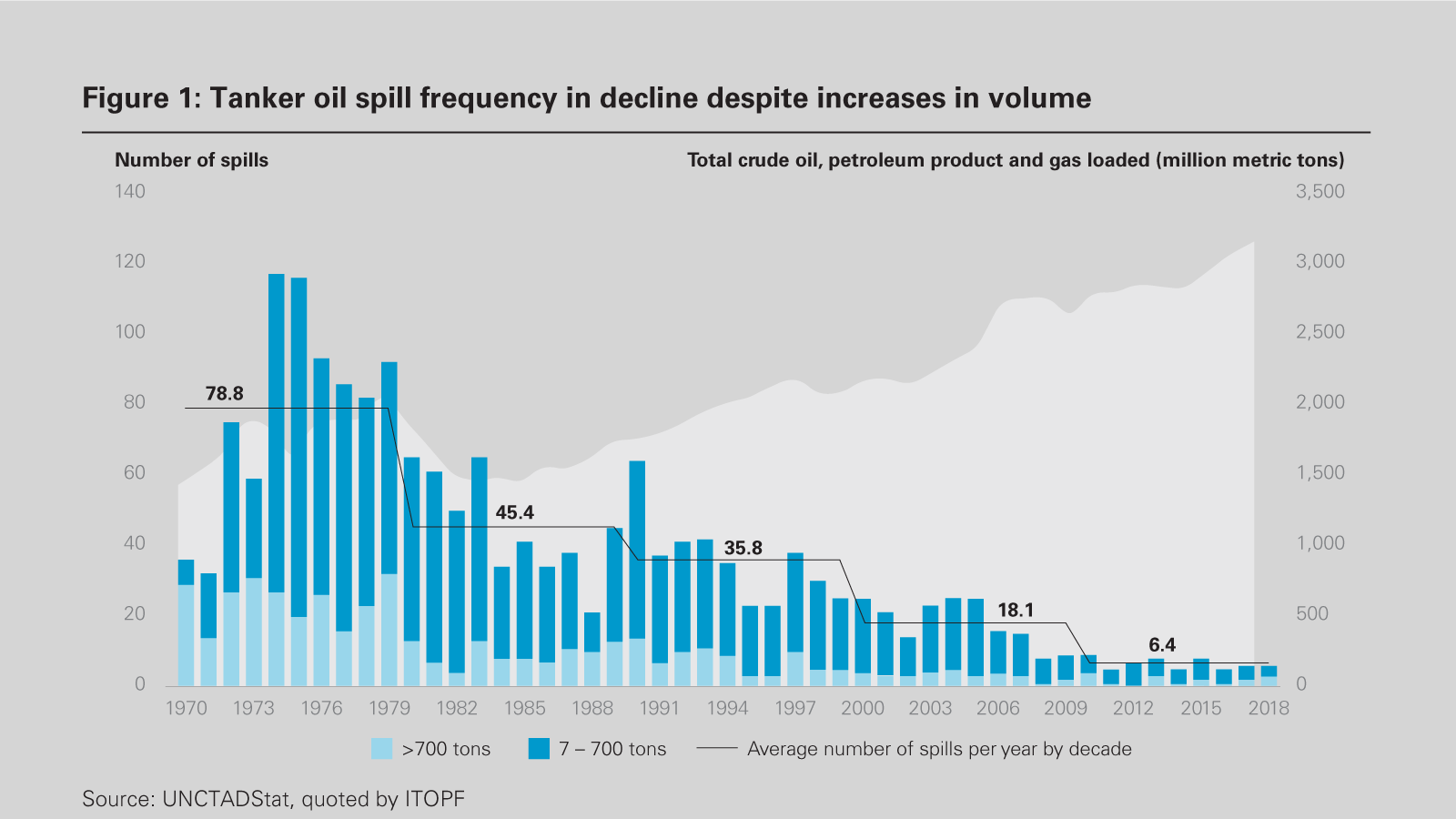

Although the shipping sector has recognized its role in environmental and social protection, and has made great strides in preventing and reacting to oil spills—which are a visible environmental impact of shipping—mitigating risks to the oceans remains a concern (Figure 1).

Another environmental impact of shipping and maritime activities is the generation of hazardous wastes and other marine pollutants from ships at sea. During normal operations, crews and passengers aboard ships produce sewage and wastewater. Historically, the typical method of disposing of waste generated on board a ship was to discharge it directly into the sea. Bilge water (i.e., any water that does not drain over the sides of the ship) may be contaminated with oil, human waste, detergents, pitch and other chemicals that may be harmful to the environment. To address this issue, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) was adopted. Since its inception in 1973, numerous annexes have addressed operational and accidental causes of ship-based pollution. For example, Annex V of MARPOL prohibits ocean dumping (other than limited wastes such as food waste). However, pollution at sea is notoriously difficult to police, and international monitoring indicates that dumping at sea persists at very significant levels.3

Oceans, coastlines, estuaries and other coastal areas may suffer from ecological damage as a result. For coastal states in Africa, marine pollution also creates negative secondary effects on human health and socioeconomic activities such as tourism, aquaculture and fishing.

Plastics are another very visible form of marine pollution that have become a source of major international concern. Although most of the plastics in the oceans originate from pollution on land and reach the sea through rivers, approximately 20 percent of the sources of plastic pollution are marine-based, through both legal and illegal dumping.4 Outside of oceanic convergence zones, which are known as floating "garbage patches" of plastics and other wastes, such debris also tends to accumulate in shipping lanes and fishing areas. Plastics are immensely durable and some persist in the marine environment for hundreds of years. Scientists are only now beginning to understand the risks of microscopic plastic fragments entering marine food chains, including bioaccumulation in apex predators and in humans consuming food from marine sources.

ATMOSPHERIC EMISSIONS

Pollution from ships is not restricted to the marine environment. Fuel used in the shipping industry is typically a heavy fuel oil that, when combusted, produces carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur oxides (SOX) and nitrogen oxides (NOX). According to the IMO, global shipping accounts for approximately 1 billion tons of CO2 annually, representing 2.6 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.5

With the rise of global trade and increased fuel consumption in the shipping industry that accompanies it, air emissions from shipping continue to rise. In May 2005, Annex VI of MARPOL took effect to address the negative impacts of air emissions from ships (from SOX, NOX, ozone-depleting substances and volatile organic compounds from shipboard incineration) and includes mandatory energy-efficiency measures to reduce GHG emissions.

Tighter emissions limits were introduced in July 2010 and, in its efforts to make shipping "cleaner and greener," in December 2017, the IMO committed to a "Respond to Climate Change Strategy" to reduce carbon emissions from ships. It has adopted a strategy for 50 percent reduction in GHG emissions by 2050 compared to 2008, looking to reach net zero emissions as quickly as possible.6

In April 2018, the IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) adopted the Initial IMO Strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from ships (the Strategy). All ships are required "to give full and complete effect, regardless of flag, to implementing mandatory measures to ensure the effective implementation" of the Strategy.7 Possible short-term measures identified include the development of technical and operational energy efficiency measures for ships; encouraging national action plans for GHG emissions from international shipping; encouraging port developments to reduce GHG emissions, including ship and shore renewable power supplies and infrastructure to support low-carbon fuels; and providing incentives to develop and adopt new technologies.

50%

reduction in GHG emissions by 2050Target set by IMO

All new ships must be built with a GHG emissions reduction of 30 percent by 2025, compared with 2014.8

By 2050, DNV GL predicts that 39 percent of shipping energy will be supplied by carbon-neutral fuels and that marine gas oil and other liquid fossil fuels, such as heavy fuel oil, will supply 33 percent of the energy used. Improvements in fuel sources will also impact carbon intensity. DNV GL expects, based on projections of demand for maritime transport work, that CO2 emissions for international shipping will decrease by 52 percent compared with 2008.9

SOX is considered one of the most harmful by-products of the combustion of ship fuel. High SOX concentrations are well recognized as a dangerous atmospheric pollutant. The IMO has consequently also introduced regulations to reduce SOX emissions from ships. These regulations, which took effect in 2005, have become increasingly stringent over time; for example, a proposed reduction of the global sulfur cap from 3.50 percent to 0.50 percent will be effective January 1, 2020 (the 2020 Limit). Under the MARPOL amendments, the carriage of non-compliant fuel oil (for combustion for propulsion or operation) is prohibited unless the ship is fitted with a scrubber system for exhaust gas cleaning. Scrubber installation is an accepted way to meet the sulfur limit requirement. Although the sulfur cap will apply globally, since the beginning of 2015, designated sulfur emission control areas have the further restriction of a lower limit of 0.10 percent.

Annex VI also introduced the concept of "Emission Control Areas" (ECA). ECAs are special zones that have limits on SOX, NOX and particulate matter. Recently, there have been calls to establish a Mediterranean ECA (Med-ECA). According to a report co-authored by the French National Institute for Industrial Environment and Risks, a Med-ECA could have significant health benefits for all Mediterranean costal states. For instance, compared to the impact of the 2020 limit on sulfur content in ship fuel, 40 percent more premature deaths are predicted to be avoidable by establishing a Med-ECA. The North African States of Algeria and Egypt are identified as two of the five main beneficiaries of these positive impacts.10

SHIPBREAKING

Another by-product of the shipping industry is "shipbreaking." Ship- breaking, or ship decommissioning, is the process by which ships are dismantled in order for their parts to be recycled or sold. On its face, as a form of recycling ships and their contents, it is considered a "green" activity. However, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has declared shipbreaking to be one of the most dangerous professions in the world. It may take place as part of an opportunistic activity, where ships are abandoned on coastlines with no controls on salvaging, or as part of organized ship recycling operations.

Nouadhibou, Mauritania has the dubious distinction of being the largest ship graveyard in the world—the coastline is a landscape of more than 300 rotting ships.

The most common form of shipbreaking is to have the vessel beached on a mudflat during high tide, where it is dismantled, typically by unskilled local workers. This method of shipbreaking, referred to as "beaching," is a dangerous industry with potentially damaging environmental and human health and safety consequences.

In countries where shipbreaking is common, any lack of regulatory oversight means there is a high risk of worker health and safety impacts, as well as unsustainable wages, forced or child labor, and other worker-related concerns. Weaker laws and enforcement provide a conducive regulatory environment for uncontrolled shipbreaking operations to flourish. End-of-life ships also contain toxic materials such as asbestos, heavy metals, oil residues and organic waste, such as tributyltin (or TBT, an extremely toxic compound used in anti-fouling paints). These pollutants require special containment, and that may not be feasible in informal breaking yards.

In addition to ship owners and flag states, national ports also have a duty to inspect foreign ships, to ensure that the condition of each ship and its equipment comply with relevant international regulations.

Even in developing countries that have applicable environmental and social standards in place, there may be a lack of enforcement of the regulatory requirements protecting worker rights or the environment, and corruption might be the prevailing way of conducting business. The monetary cost savings from beaching are ultimately represented by harm to human health and the environment, as well as socioeconomic impacts to livelihood from tourism or fishing.

Nouadhibou, Mauritania has the dubious distinction of being the largest ship graveyard in the world. For several decades, end-of-life ships have been abandoned there, and the coastline is now a landscape of more than 300 rotting ships. This number continues to grow each year as a thriving salvage industry has emerged, contributing to speculation that large-scale beaching practices could move to parts of coastal Africa as the location of choice. Potential host African coastal states could benefit from end-of of-life vessel recycling without compromising human health and safety and environmental protection, as there are international protocols addressing the ship recycling industry.

The Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships (2009) (Hong Kong Convention) requires that the recycling of ships must not pose unnecessary risks to human health, safety and the environment. To date, the Hong Kong Convention has only been ratified by seven countries and therefore has not taken effect. It will only enter into force two years after certain criteria for its ratification have been met, including the requirement that 15 countries, representing 40 percent of the world's merchant shipping by gross tonnage, ratify the agreement. The only African country to have ratified the Hong Kong Convention is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nonetheless, the IMO has issued the Guidelines for Safe and Environmentally Sound Ship Recycling (2012) (the 2012 Recycling Guidelines). These align with the Hong Kong Convention, so meeting these guidelines represents good international industry practice and will prepare ship owners and recyclers to be in compliance with the Hong Kong Convention when it takes effect. This has the added benefit of protecting workers and the environment in African countries.

Under the waste law regime of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (Basel Convention), end-of-life vessels are considered hazardous waste. Through the EU Waste Shipment Regulation,11 the EU has transposed into community law the "Basel Ban" Amendment, which prohibits any export of hazardous wastes from a developed (OECD) country to a developing (non-OECD) country. As a consequence, if an end-of-life vessel is flagged to a developed country, it should therefore not be transported for disposal to any developing country, in Africa or elsewhere.

30%

of the Seychelles is in the process of being designated a Marine Protected Area (MPA)

To avoid complying with these prohibitions, some ship owners resort to transferring end-of-life vessels to dealers or other intermediaries once the vessel has left EU territory or is on the high seas.12 The ship may then be sold to a shipbreaking yard or abandoned at places like Nouadhibou, in contravention of the Basel Convention.

Scrap dealers may also seek to change the flag of the ship to disguise its origin, making it more difficult to practically enforce international requirements. Low registration standards combined with minimal vetting of ships creates a higher risk that vessels flagged to countries that have less stringent registration requirements are operating in breach of international standards. Registries therefore play a key role in managing requirements such as environmentally sound ship decommissioning as well as human rights obligations more broadly.

In 2009 the IMO introduced the innovative concept of a "Green Passport," requiring ship operators to provide information about all the materials aboard the ship that were known to be potentially hazardous. In 2011, the IMO introduced the concept of an International Certificate on Inventory of Hazardous Materials (IHM) to replace the Green Passport. The IHM is specific to each ship and must contain information about any hazardous material in the structure of the ship or its equipment, generated through operations or stored on the ship.

The 2012 Recycling Guidelines require the development of a ship recycling plan (SRP) to ensure that the ship owner and ship recycling facility work together on management of hazardous materials, safety procedures, dismantling sequences and any other elements to ensure compliance with the Hong Kong Convention requirements.

The IHM and the SRP are crucial developments in ensuring that ship builders, operators and recyclers are all responsible for decommissioning ships in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. With improved information about hazardous materials, recyclers are able to use advance planning to reduce or eliminate environmental contamination and social risks. In addition, by having a transparent, ongoing reporting system of this kind, both operators and recyclers can ensure that they are providing for and mitigating any risks of liability for environmental contamination or harm to humans.

Finance providers are beginning to understand their role in ending poor shipbreaking practices and other environmental and social impacts on Africa's maritime and coastal environments. By conducting proper due diligence in relation to the flag state of the ship, the flag of the port state and monitoring of compliance with Green Passport/IHM requirements, financiers can support covenants and conditions for end-of- life operations to be conducted in countries where environmental protection and human rights issues are regulated, and decommissioning is undertaken by recycling facilities operating in an environmentally and socially responsible manner (e.g., in accordance with the Hong Kong Convention or, if EU flagged, the Waste Shipment Regulation).13

POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTS IN AFRICAN PORTS

Africa ports have taken positive steps toward complying with international environmental standards concerning waste management. Recent examples include:

Tanzanian Ports Authority

Working to reduce pollution levels at Dar es Salaam through a port expansion and rehabilitation initiative

Working to reduce pollution levels at Dar es Salaam through a port expansion and rehabilitation initiative

Port Elizabeth Harbour in South Africa

Introduced an environmental protection program, requiring a waste management plan to be developed and implemented

Introduced an environmental protection program, requiring a waste management plan to be developed and implemented

Port of Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire

Achieved ISO 14001 certification in 2017 for its environmental management system

Achieved ISO 14001 certification in 2017 for its environmental management system

"BLUE FINANCE" AND THE ROLE OF LENDERS

Over the past ten years, lenders have become increasingly aware of environmental and human rights issues. In a concerted international effort for investments to move toward environmental sustainability, international institutions have been developing green industry standards. The most well-known green financing standards are the Green Bond Principles, established by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) in 2014. Green bonds are any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance "green" projects (e.g., environmental protection, sustainability, climate change solutions and renewable energy projects). The green bonds market has exponentially increased since the Green Bond Principles took effect. In May 2018, the world's first shipping sector-labeled green bond was issued by Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK). Designed to support NYK's management plan, "Staying Ahead 2022 with Digitalization and Green," it aims to integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles for sustainable development using the funds for new and existing projects in NYK's "Roadmap for Environmentally Friendly Vessel Technologies." This includes liquefied natural gas (LNG)-fueled ships, LNG bunkering vessels, ballast water treatment equipment and SOX scrubber systems.

As the "Green Economy" develops, gaps for the sustainable management of oceans have appeared, giving rise to the concept of the "Blue Economy," which is defined by the World Bank as "sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, and ocean ecosystem health."14 The Blue Economy encompasses activities in the renewable energy, tourism, climate change, fishing, waste management and maritime transport sectors.

"Blue Finance" is still an emerging concept. However, the Seychelles has become the first country in the world to put Blue Finance measures into effect. In 2016, the Nature Conservancy, through its investing arm NatureVest, developed a US$22 million sovereign debt conversion for the Seychelles. Through this, approximately 30 percent of the Seychelles is in the process of being designated a Marine Protected Area (MPA).

In October 2018, the Seychelles became the first entity to issue a sovereign Blue Bond to expand its MPAs, improve the governance of fisheries and develop the Seychelles' Blue Economy. The US$15 million Blue Bond is partially guaranteed by the World Bank and supported by the Global Environment Facility. In addition to being a major milestone in Blue Finance, the Seychelles' Blue Bond provides strong evidence that sustainable development of the Blue Economy is possible, as well as mutually beneficial for international investors.

To ensure the sustainable use of oceans and their resources, in March 2018, the European Commission, World Wildlife Fund, the UK Prince of Wales's International Sustainability Unit and the European Investment Bank (EIB) jointly released a set of voluntary Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles (the Blue Principles). Without duplicating existing frameworks, the Blue Principles are intended to implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals, especially those that contribute to the management of the oceans (e.g., SDG 12 on responsible consumption, SDG 13 on climate action and SDG 14 on life below water). The Blue Principles are also intended to comply with IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability and the EIB Environmental and Social Principles and Standards.

AFRICA'S SHIPPING INDUSTRY IS MAKING PROGRESS

With the rapid expansion of the African maritime industry, African countries have an opportunity to become world-class leaders in sustainable shipping practices. One means of ensuring the development of Africa's maritime industry is by increasing resources and capacity-building to strengthen institutions responsible for policing environmental and social legislation. Protecting marine and coastal ecosystems in Africa is essential for achieving the international commitments that African countries have made and for protecting the health and welfare of coastal populations, biodiversity and for socioeconomic progress.

1 Saggia, Gilbert. (2017). About 90% of Imports and Exports in Africa Driven by Sea at http:// www.news.sap.com/Africa/2017/11

2 https://www.liscr.com

3 Greyer, R. (2017) "Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made," Science Advances.

4 Greyer, R. (2017) "Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made," Science Advances.

5 http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/ PollutionPrevention/AirPollution/Pages/ Greenhouse-Gas-Studies-2014.aspx

6 International Maritime Organization, "UN body accepts climate change strategy for shipping" available at: http://www. imo.org/en/mediacentre/pressbriefings/ pages/06ghginitialstrategy.aspx

7 https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/ resource/250_IMO%20submission_ Talanoa%20Dialogue_April%202018

8 International Maritime Organization, "Low carbon shipping and air pollution control." Available at: http://www.imo.org/en/ mediacentre/hottopics/ghg/pages/default.aspx

9 DNV-GL, "Energy Transition Outlook, Maritime Forecast to 2050" available at: https://eto. dnvgl.com/2018/maritime

10 French National Institute for Industrial Environment and Risks, "ECAMED: a Technical Feasibility Study for the Implementation of an Emission Control Area (ECA) in the Mediterranean Sea." Available at: https:// www.ineris.fr/sites/ineris.fr/files/contribution/ Documents/R_DRC-19-168862-00408A_ ECAMED_final_Report_0.pdf

11 Regulation (EC No 1013/2006)

12 https://www.iims.org.uk/ dirty-and-dangerous-shipbreaking/

13 EU Regulations on Shipments of Waste (EC No. 1013/2006)

14 http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/ infographic/2017/06/06/blue-economy

2 https://www.liscr.com

3 Greyer, R. (2017) "Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made," Science Advances.

4 Greyer, R. (2017) "Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made," Science Advances.

5 http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/ PollutionPrevention/AirPollution/Pages/ Greenhouse-Gas-Studies-2014.aspx

6 International Maritime Organization, "UN body accepts climate change strategy for shipping" available at: http://www. imo.org/en/mediacentre/pressbriefings/ pages/06ghginitialstrategy.aspx

7 https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/ resource/250_IMO%20submission_ Talanoa%20Dialogue_April%202018

8 International Maritime Organization, "Low carbon shipping and air pollution control." Available at: http://www.imo.org/en/ mediacentre/hottopics/ghg/pages/default.aspx

9 DNV-GL, "Energy Transition Outlook, Maritime Forecast to 2050" available at: https://eto. dnvgl.com/2018/maritime

10 French National Institute for Industrial Environment and Risks, "ECAMED: a Technical Feasibility Study for the Implementation of an Emission Control Area (ECA) in the Mediterranean Sea." Available at: https:// www.ineris.fr/sites/ineris.fr/files/contribution/ Documents/R_DRC-19-168862-00408A_ ECAMED_final_Report_0.pdf

11 Regulation (EC No 1013/2006)

12 https://www.iims.org.uk/ dirty-and-dangerous-shipbreaking/

13 EU Regulations on Shipments of Waste (EC No. 1013/2006)

14 http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/ infographic/2017/06/06/blue-economy

View full image

View full image View full image

View full image

Comments

Post a Comment